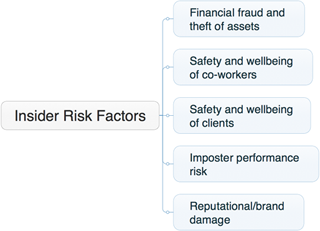

In enterprises of all kinds, whether private, public or not-for-profit, we manage risk.

Risk comes in many forms – strategic, financial, operational, environmental. This review of evidence focuses on a particular type of risk that increasingly occupies the minds of managers and has as much potential to derail our corporate plan as any other. We’ll refer to it as Insider Risk. It concerns people. The people we hire.

Financial fraud and theft of assets

PwC’s Global Economic Crime Survey 2016 reports that 55% of UK respondents reported experiencing economic crime in the last 24 months, with 31% of fraud being committed by internal perpetrators. Looking further into the seniority breakdown of this group, PwC found that 28% of internal fraud was committed by Junior Staff, 36% by middle management and a striking 18% by senior management.

Separately, in a review of recorded thefts by employees statista.com reports that the number of police-recorded ‘theft by an employee’ offences in England and Wales was 10,347 in 2016/17.

Safety and wellbeing of co-workers

The Health and Safety at Work etc Act 1974 (HSW Act) makes it clear that employers have a legal duty to ensure, so far as is reasonably practicable, the health, safety and welfare at work of their employees.

In a post-Weinstein era, it’s clearer than ever that enterprises owe it to their staff to ensure that the person sitting at the next desk does not pose a risk to their safety and wellbeing. This is not a new concern as research from the Academy of Management (http://aom.org) illustrates.

More recent figures from the crime survey of England and Wales show that 8% of assaults and 12% of threats experienced at work in 2015/16 were from colleagues.

Safety and wellbeing of clients and their customers

A parallel risk is that posed by rogue employees to clients and their customers. Many enterprises assume that they’re not legally responsible for the actions of employees toward individuals. However, in 2016 the UK Supreme Court gave judgment in the case of Mohamud v Wm. Morrison Supermarkets plc, confirming that an employer can be held liable for an assault on a customer.

Beyond legal responsibility there is, of course, moral responsibility. Knowingly or by omission exposing third parties to risk of financial, physical or emotional harm would be considered unacceptable by most of us, which relates to reputation and brand, which we’ll consider last.

Imposter performance risk

Performance risk is inherent in inviting a new colleague into an organisation. We mitigate that risk by crafting induction processes to help new employees acquire understanding of organisational and brand frameworks. We describe ‘learning curves’ to model the acquisition of knowledge and experience needed to turn the new employee into a fully productive member of the team

But if that new employee is not the person they purport to be, performance risk is raised to a whole new level, especially if the new employee occupies a senior position.

In December 2017, the Daily Mail reported on an oil industry executive who had falsely claimed academic qualifications and research publication credits to land a Managing Director position with a Darlington engineering company. The deception was discovered after many months when the individual’s performance in his role failed to meet the standards expected, putting strategically important contracts at risk. The judge, in his summing up in the resultant criminal trial stated “… had the firm not promptly discovered his deceit it could have cost them contracts worth millions.” The erstwhile MD was given a 12-month custodial sentence.

Reputational/Brand damage

Your brand can and should be your most valuable asset, and reputation is a major component of brand value – the extent to which the community feels it can rely on your enterprise to deliver quality products and services consistently and safely.

And yet, according to Harvard Business Review “Most companies, however, do an inadequate job of managing their reputations in general and the risks to their reputations in particular. They tend to focus their energies on handling the threats to their reputations that have already surfaced. This is not risk management; it is crisis management—a reactive approach whose purpose is to limit the damage.”

Recent research by Nielsen underlines that employees are a company’s greatest assets when it comes to reputation management. “From a reputational perspective, employees can play a big role in both protecting against and introducing risk.”

Mitigation

The bad news is that we can never be absolutely sure that bringing new hires into an organisation won’t expose us to one or more of the above risks. The good news is that there is one single mitigation that eliminates the largest constituent element. Screening ensures that the people you hire are representing themselves with honesty and integrity. Failing to adequately screen incoming employees exposes your reputation and your brand to uncontrolled risk.